Strategy Beyond the Hockey Sticks, written by Chris Bradley, Martin Hint and Sven Smith, consultants at McKinsey, builds on the authors’ experience developing winning strategies, combined with detailed research and analysis of more than two thousand firms. It uses real life examples alongside fairly humorous cartoons to drive home its points. We do love those cartoons 😂

The authors use the hockey stick analogy to illustrate the fact that strategists often predict that their strategy may result in a short dip in profits while investing in getting their things off the ground, followed by a dramatic rise as their strategies are implemented. In other words, the strategy is overly conservative for the first couple of years, then overly aggressive longer-term. The hockey stick can be seen graphically if expected profit is plotted against time. As the authors show, the projected dramatic rise in profits rarely happens in practice.

Strategy development is usually done in teams; hence it is a social undertaking, with the disadvantages that it is subject to social biases – halo effect, anchoring, confirmation bias, champion bias and loss aversion. The authors point out how, in developing strategy, managers may act in their own interest, rather than that of the business and its stakeholders. The social side of strategy also causes strategy development to lean towards caution and the status quo.

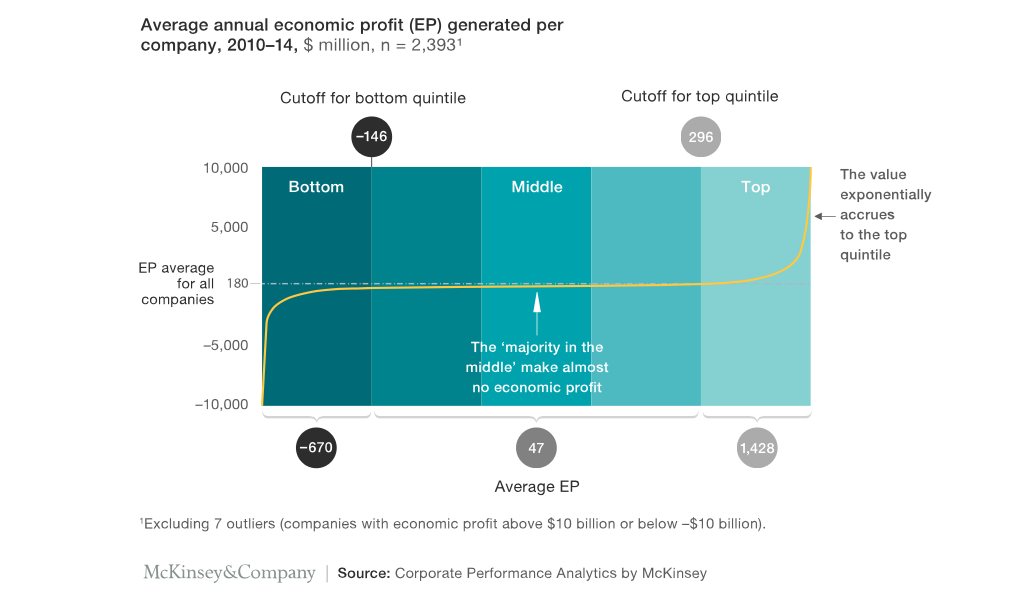

The authors hold that economic profit provides the best measure of business performance. This is the total profit after the cost of capital is subtracted. The authors plotted the average economic profit of 2,393 companies and found that they resulted in a Power Curve – the tails of the curve rise (and fall) at exponential rates. What is startling is that the majority of companies, in the middle, make almost no economic profit. Where you need to be is in the top quintile of the power curve, ideally in the top 8%.

Your strategy should move you up the power curve, instead of keeping you in the flat middle. Businesses operate in an atmosphere of uncertainty; the danger is that they develop strategies that result in bold forecasts but timid plans and risk adverseness, keeping them in the flat middle. Your strategy needs bold targets that are anchored in the realities of the business and the context it operates in.

Note that industries also have a power curve – the authors plot average annual profit of firms within each industry and show a similar pattern, with Software and Technology Hardware being in the top percentile and Electric Utilities and Construction Materials being lowest.

Strategy is about dealing with uncertainty. An assessment of your odds of success – competitive, market, regulatory – needs to be part of your strategic calculation. You need to improve both growth and return on invested capital. You need to think in terms of probabilities. Your strategy needs to factor in the probability of success and hence of moving up the power curve and hockey stick.

Through their analysis the authors have identified ten levers that were the strongest determinants of success. They grouped them into three categories:

- Endowment – what you start out with

- Trends – the winds pushing you along or pushing against you

- Moves – what you do; the key thing is to make big bold moves relative to your competition

The authors’ model, based on endowment, trends and moves, gives a good indication of the probability of a strategy being successful. In analysing the odds of moving along the power curve, the authors found that endowment determines about 30%, trends 25% and moves 45%.

Endowment

In terms of your Endowment, i.e. your starting point, three things are important.

- The size of your company – the larger your company is, the higher the likelihood of improving your position in the power curve

- Debt level – the less debt you have, the better your chance of improvement

- Investment in Research and Development – your ratio of R&D to sales needs to be in the top half of your industry

Trends

The two significant Trends are industry trend and exposure to growth economies. The trend in your industry is the single most important of all the ten levers. Your industry needs to be moving up the Industry Power Curve, which shows growth in economic profit across all companies in the industry. To capitalize on the growth economies trend, you should be doing business with faster-growing emerging economies.

You need to identify all relevant trends and make big innovative Moves to get ahead of them. The book discusses how to recognize, adapt to, and profit from, changing trends. By the way, the trends may be unfavourable, in which case you may need to divest parts of your business or move to a different industry. The critical success factor is to make big moves, focusing resources in a limited number of places where they can make most difference.

Moves

The authors identify five big moves and show how strategy is most effective when a number of these are combined. It is also critical that the moves you make take you ahead of the industry average, as your competitors will also be making moves.

Move 1: Programmatic M&A – mergers and acquisitions

The first move is Programmatic M&A – mergers and acquisitions. A key indicator of success is a steady stream of mergers and acquisitions, each costing no more than 30% of your market capitalization.

Move 2: Dynamic allocation of resources

With this move, instead of being spread evenly across the business, investment needs to be focused in areas where it can lead to success. Feed the units that could produce a major move up the power curve, while reducing resources in those units unlikely to surge.

Move 3: Strong capital expenditure

With the next move, you should be thriving to be in the top 20% of your industry in your ratio of capital spending to sales.

Move 4: Productivity

You should be improving productivity consistently faster than your competitors.

Move 5: Improvements in Differentiation

Can you develop a sustainable cost advantage or charge premium prices because of product differentiation or innovation?

Strategy into action

The book ends with a chapter on how to turn your strategy into action, which calls for eight big shifts.

-

Move from annual planning to strategy as a journey. You should hold regular strategy discussions with your leadership team, reviewing a list of the most important strategic issues and initiatives, making adjustments as necessary. You should move to a 12-month rolling plan of initiatives.

-

Discuss real alternatives – compare real alternate plans with different risk and investment profiles; track assumptions over time and build contingencies into your plans so that you can evolve your choices as you learn more

-

Pick the likely winners. Identify the breakout opportunities early and give them the resources they need, if necessary taking from areas with lower chances of winning. Adjust your team’s incentives to encourage resource re-allocation instead of resource hoarding.

-

Go from approving budgets to making big moves. Because of the social dimension of strategy creation that we mentioned at the beginning, there is a real danger that your strategy creation sessions degenerate into a process of setting budgets for the next few years. You need to break out of this mindset and get to making big moves. One way to do this is to build a “momentum case”. This is a simple version of the future that presumes your business’s current performance is going to continue as it has been going. This will anchor you in reality. You can then see how much difference your big moves need to make.

Do a “tear-down” (a McKinsey phrase for taking things apart to understand the detail of how they work) of your past business results to see what came from trends and what from big moves. Check that your strategic plan is big enough to plug the gap between the momentum case and where you want to be.

Benchmark your moves – compare them to competition to test that they are really big enough to make the difference you are seeking. Focus on moves first, budgets second.

-

Go from budget inertia to liquid resources. To mobilize resource and budgets for big moves, you need a certain amount of resource flexibility. To get this, start freeing up resources as much as a year before you will need to deploy them. Create a pool of resources that can be moved onto big moves, as needed.

-

Move from sandbagging to open risk portfolios. Business unit leaders often pad their forecasts to improve the odds of meeting their targets; this is sandbagging. Instead of aggregating individual padded budgets, manage one corporate-level portfolio that is based on a series of big moves. Manage risk at this level and adjust incentives to reflect the risk people are taking.

-

Big moves will be risky and some may fail. Reward people for the true quality of their effort, even if their move fails. Where moves are risky, use team incentives that reflect the probability of success, over longer time-horizons.

-

Go from long-range planning to forcing the first step. Create short term (6 month, quick win) initiatives to get going and build momentum. At first, focus more on actions than results. Monitor your short and longer-term initiatives in a rolling plan.

Although this highly recommended book is based on the authors’ experience of larger companies, the lessons also apply to medium and smaller companies.