What is Reverse Innovation?

Reverse Innovation is about innovating to serve the poorer populations of the world, which have third world constraints, and applying those innovations back into developed economies. There are significant lessons to be learnt for businesses in the developed world on how growth could be driven by looking further afield.

An Example of Reverse Innovation

Well over 20 years ago, the manufacturer of heavy machinery Siemens was faced with a challenge when it came to selling it’s products in India. The impediment to increasing its market share was that the equipment needed regular maintenance. For reasons of distance, skills and logistics, this was difficult, so the company charged its engineers with the task of developing a version of its equipment that required less or no maintenance, which they succeeded in doing. This approach worked so well that the company incorporated the maintenance improvements into the equipment being sold to their regular customers in the developed world, allowing them to reduce prices and increase profit and market share.

The Bottom of the Pyramid

The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid by the late economist C K Prahalad, discusses a number of other companies and public sector organizations that had created successful business initiatives in developing economies.

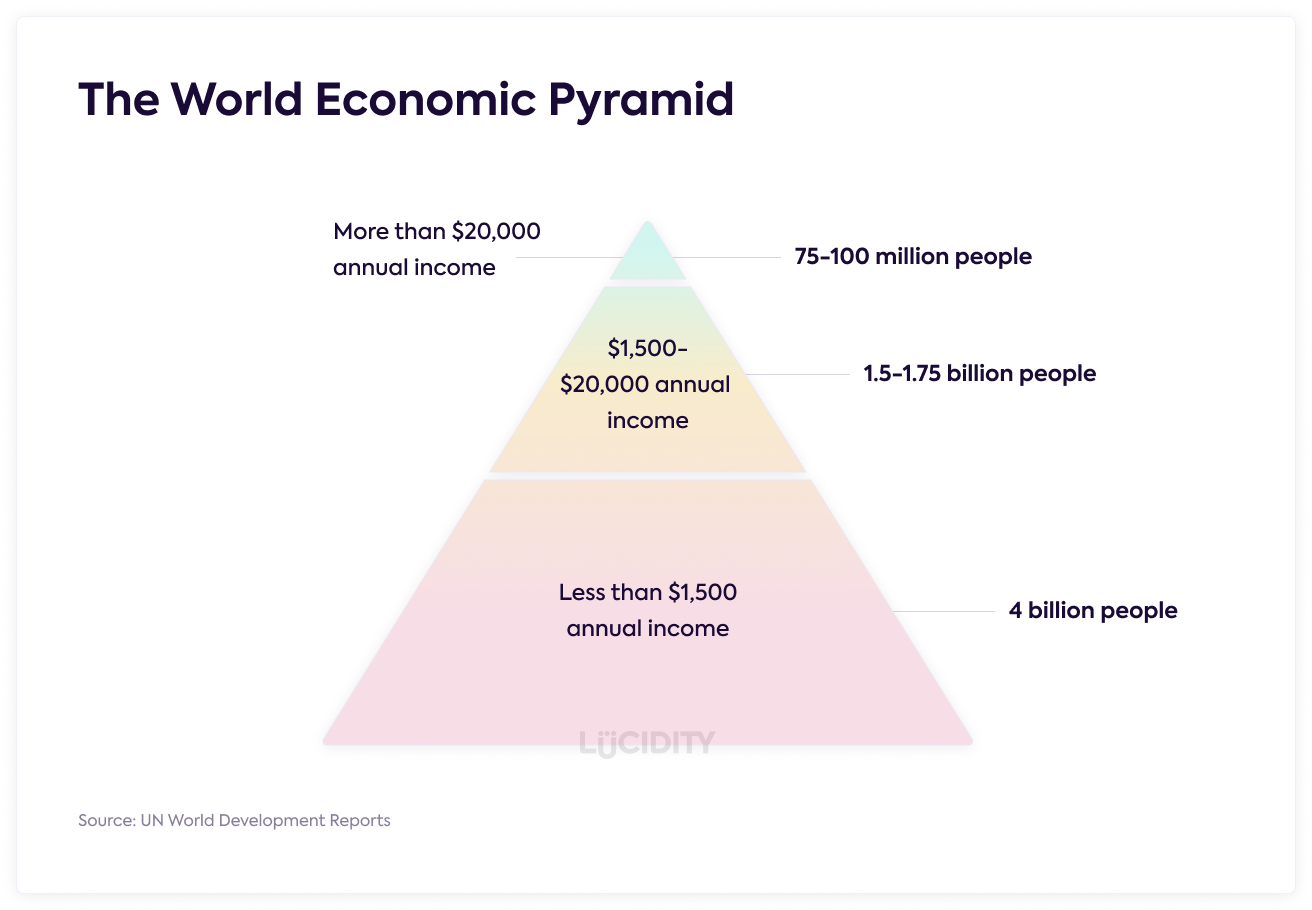

The pyramid (in reality a triangle) is illustrated by a diagram in Prahalad and Hart’s 2002 paper in Strategy+Business quarterly . It divides the world’s population into tiers, based on purchasing power. Most of the world’s population is in the bottom tier of this pyramid, some living on as little as two dollars a day. Although the intervening twenty years has seen over a billion people move out of extreme poverty, there are still 3.5 billion people in the bottom category, while the idea of the world’s poor as a profitable market for innovation and the appropriate business models has gained acceptance.

Professor Prahalad’s contention was that consumers at the bottom of the pyramid (BoP) represent a vibrant consumer market which could be addressed by for-profit business models, and that the poor had to be partners in the process. He argued that the poor aren’t much different from those further up – they still want quality products, are very brand-conscious and, naturally, value-conscious.

Furthermore, they will spend their limited income on aspirational products, a view which has been vindicated by the widespread take up of mobile phones by people at the bottom of the pyramid. In fact, the wide availability of mobile phones has led to technology solutions that leapfrog those available in developed countries.

An Example of BoP Innovation

For example, Vodafone and Safaricom developed M-Pesa (M for mobile, pesa is Swahili for money), a mobile phone-based money transfer service, payments and micro-financing service, which has spread from Kenya to several other African countries. M-Pesa allows users to deposit, withdraw, transfer money, pay for goods and access credit and savings, all with a mobile device.

Reversing Those BoP Innovations

When those innovations in BoP markets are then “reversed” and brought to the industrialised world, that is Reverse Innovation. The term was popularised by Professors Vijay Govindarajan and Chris Trimble, who later published the book Reverse Innovation: Create Far From Home, Win Everywhere. Reverse Innovation is all about developing products created through inexpensive methods and processes and then repackaging them as low-cost goods in the developed world.

A complementary concept is Jugaad Innovation, described in Jugaad Innovation: Think Frugal, Be Flexible, Generate Breakthrough Growth by Radjou, Prabhu and Ahuja. Otherwise known as frugal innovation, this is about flexible, agile innovation and a mindset of frugality and improvisation.

All three books contain many examples of innovation in emerging markets that are driving better products in developed markets.

Why is Understanding Reverse Innovation Important?

Listen to Jeffrey Immelt, at the time CEO of the US multinational General Electric Company “If we don’t come up with innovations in poor countries and take them global, new competitors from the developing world – like Mindray, Suzlon and Goldwind – will. That’s a bracing prospect. GE has long had tremendous respect for traditional rivals like Siemens, Philips, and Rolls-Royce. But we know how to compete with them. They will never destroy GE. The emerging giants, on the other hand, very well could”.

Who are these competitors? Mindray are based in Shenzhen, China, produce medical devices and compete with GE Healthcare. Goldwind are from Beijing, specializing in renewable energy and are competition for GE Energy. Suzlon “Born in India, Embracing the World” was set up by Tulsi Tanti when he found energy was 40-50% of his textile factory costs and supply was unpredictable; he tried various solutions and settled on wind power.

More Examples of Reverse Innovation

An early example of reverse innovation is the Gatorade story. “We didn’t have Gatorade” was the explanation given by the coach of Georgia Tech’s American football team for losing to the University of Florida in the 1967 Orange Bowl. Gatorade was a tasty drink that speeded up the replenishment of electrolytes and carbohydrates that players lost through sweat and exertion.

The origin of Gatorade lay in epidemics of cholera in Bangladesh. The key to keeping cholera patients alive was to keep them hydrated. Western doctors went there to help and found a centuries-old local remedy for diarrhoea caused by cholera was a concoction that included things such as coconut water, carrot juice, rice water, carob flour and dehydrated bananas. Western medicine thought carbohydrates would cause bacteria to multiply and the cholera to get worse; yet for thousands of years, this was the normal treatment used in Ayurvedic medicine. By giving carbohydrates and sugar in the solution with salt, uptake was quicker and patients rehydrated faster.

This finding was written up in the Lancet, a world-leading peer reviewed medical journal. A common problem between cholera and sports medicine was – rehydrating rapidly; a doctor in the University of Florida created Gatorade, a reverse innovation, adopted first in the developing world. Why Gatorade? The University of Florida sports teams are known as the “Florida Gators” – there are lots of alligators in Florida. Gatorade was bought by Pepsico in 2001.

In the late 1990s, Louis Schweitzer, CEO of Renault, visited Russia, where he found that low-cost cars like the antiquated Lada were outselling his company’s much more expensive cars. Schweitzer challenged his research and development team to come up with a modern, reliable and affordable car at the same price as the Lada. The result was the Dacia Logon, a no-frills small family car produced by both Renault and its Romanian subsidiary Dacia, at a price point lower than the Lada. Since its launch, the Dacia Logan is estimated to have reached over 4 million sales worldwide, and Renault have become practitioners of “frugal engineering”.

The Five Paths of Reverse Innovation

The authors of Reverse Innovation have identified five gaps in emerging markets; innovation can address these gaps and provide opportunity.

The Performance Gap

Developing world customers cannot afford top performance, but you cannot just export cut-down rich world products and services. An entirely new price-performance curve is needed.

At one stage Nokia achieved a 60% market share in India. They re-imagined the mobile phone. They cut costs by having only a few basic models, added Hindi text messaging by using software, not hardware, which was far less costly. They also added useful functionality to the handset, such as a flashlight, that appealed to rural customers with irregular electricity.

The Infrastructure Gap

Rich countries have highly developed infrastructure – roads, telecoms networks, power plants, schools, universities, hospitals, banks, stock markets etc. There is much less such infrastructure in developing countries.

However, poor countries are on a different development path than the rich world – they do not need to go through the same phases of development. Instead some are leapfrogging the rich world in technologies such as mobile communications. We saw earlier how M:Pesa mobile financial services in Africa turns your mobile phone into your virtual bank.

GE Healthcare are a big seller of high end electrocardiogram (ECG) machines; these are only affordable by the top hospitals in India. GE India created an innovative electrocardiograph suitable for rural doctors – light, affordable, addressing the local requirements of portability (so doctors could take the ECG to their patients rather than requiring the patients to come to a medical facility), battery power, ease of use and ease of maintenance and repair.

The Sustainability Gap

There is an ongoing conflict between economic activity and the environment. One example is extreme air pollution in Beijing. In spite of their reputation for burning coal to generate electricity, the Chinese are making huge investments in sustainable technology. For example, BYD (Build Your Dreams www.byd.com) is a company based in Shenzhen who have developed a range of plug-in electric vehicles with Li-ion iron phosphate batteries. Their Polestar car was hailed by Top Gear Magazine as “One of the most complete electric cars money can buy. Superb build quality, and decent to drive”. BYD are also active in solar energy and LED lighting. They have taken their solutions worldwide.

The Regulatory Gap

Regulatory systems are a double-edged sword. Regulations are often necessary to prevent or correct abuse but they can grow into barriers to innovation. There is less regulation in the developing world, which may lead to less bureaucracy and faster progress, but can also lead to dangers to employees and the public.

In the developed world, routine monitoring of liver function for patients on Antiretroviral drugs and many other medicines is the accepted standard of care. Monitoring for liver toxicity in the developing world, however, is severely limited by expense and access to modern instrumentation. Because of these obstacles, many developing world patients receive minimal or no monitoring during treatment.

Diagnostics For All (dfa.org) is a not-for-profit company founded at Harvard University in 2007 by a group of scientists and entrepreneurs with a shared commitment to saving lives and alleviating disease in developing countries and other resource-poor settings through low-cost, innovative, practical diagnostic devices. They developed a low-cost, patterned paper-based, liver enzyme diagnostic test that can provide an assessment of liver health from a single drop of blood in about 15 minutes. This was tested in Vietnam, where less strict regulation facilitated more rapid testing and prepared the company to meet more stringent US FDA regulations.

Diagnostics For All were subsequently awarded a grant by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to develop a low-cost, rapid diagnostic test for immune markers of successful vaccination against tetanus and measles. The development of a simple, point-of-care immunity assessment will have immediate impacts on current global efforts to control vaccine-preventable diseases. The company has developed other low cost, simple and rapid diagnostic tests for use in healthcare and agriculture.

The Preference Gap

Consumers have different preferences in different cultures. Pepsico developed lentil-based snacks in India to meet local demand. In 2003 Procter and Gamble introduced VickMiel, a new over-the-counter cough medicine for low-income consumers in Mexico. This used natural honey, rather than artificial flavours. After a couple of years P&G brought this product to developed countries, at a lower price than its Vicks product, with considerable success.

The lessons learned from the five gaps are that developing markets have problems not already solved in the rich world; poor countries have modern technologies that were not available when rich countries addressed similar needs. From this we can see a need to start from scratch when tackling these problems, to undertake what is called Clean-slate innovation.

A key finding is that reverse innovations can “flow uphill” into mainstream markets, posing a huge danger for incumbents. The products may not be attractive on the day they are introduced, but they will catch on if they close the needs gap. They may sneak up on incumbents and leave them behind. An example is GE Healthcare’s Vscan. This is a battery-powered ultrasound scanner, developed in China to meet Chinese market needs: ultra-low cost, portability, ease of use. It is now available in US, Europe, India, China, Japan and Canada. In this case the incumbent, GE, capitalized on the reverse innovation, rather than being overtaken by competitors.

Traditional Attitudes to Selling into Poorer Markets and Why They’re Flawed

What should Multinationals do to counter reverse innovation? It is critical to change mindsets in multinational companies. There is a mindset known as dominant logic. The way they think has been built up from their experiences and how they operated in the past. You need a new mindset to succeed in emerging markets.

There are five levels of dominant logic when it comes to selling into poor countries, which you can see as a ladder of denial (or enlightenment, perhaps):

Level 1: Poor countries are irrelevant – this attitude is not prevalent any longer

Level 2: Sell to the top of the pyramid. This assumes that developing economies are gradually catching up and following same path of development as rich world. However, emerging economies are now using 21c technology to address their 21c challenges. They are not at all on path of development taken by the West, and historical best practices won’t work

Level 3: We develop great products at home; we can sell them round the world with minor modifications, often stripping out function to reduce cost. This is known as glocalization – it still dominates.

In contrast, the Godrej Group (godrej.com) came up with a disruptive innovation, working with Innosight, an organization founded by Harvard professor Clayton Christiansen to promote Disruptive Innovation. The context of food storage is much different in India; electricity supply cannot be guaranteed. Godrej’s chotuKool fridge was designed for people in the rural areas of India. It was originally priced at $69, making it the world’s cheapest fridge. It doesn’t use a compressor, only a cooling chip and a fan run on batteries. It has only 20 parts. The designers involved villagers right from design to selling of the product. An additional benefit is that chotuKool has helped increase the income of self-help groups that work as the distribution network.

Level 4: Emerging markets have vastly different needs, so you need to design new products from scratch.

You also need to avoid three traps.

- Believing that people on low incomes will be satisfied with low quality

- Targeting the lowest price point – China’s energy initiatives driven by sustainability, not cost

- Reverse Innovation is not confined to product innovation; you can have other types of innovation – e.g. business model, process, platform innovations

Level 5: Think global, not local. Take your innovations out into the world. Indian IT suppliers Infosys, Tata Consulting Services, Wipro and others use low cost (at present) staff to do lot of IT services from India. This forced IBM and Accenture to put lot of work into India, China, Brazil, Argentina, Eastern Europe. Brazilian aerospace manufacturer Embrear identified gaps in the market for certain mid-capacity planes and developed appropriate offerings. Cemex from Mexico is now the second largest building materials company worldwide, operating in over 50 countries.

How to Respond to the Threat of Reverse Innovation as a Business in the Developed World

To survive against Reverse Innovation, as a multinational, you need to create and support Local Growth Teams. These are small cross functional entrepreneurial units, physically located in the emerging market with a full set of business capabilities and authority to set strategy and develop products and services. They operate like a Lean Startup, carry out clean-slate needs assessments, build clean-slate solutions and use a clean-slate organizational design. They should also leverage the parent companies’ global resources.

If you’re a small or medium company with limited global range, what should you do? You should

- Adopt a reverse innovation mindset,

- Look to strip out cost while maintaining product and service quality,

- Carry out clean-slate needs assessments by involving your customers and potential customers,

- Apply clean-slate innovation in co-creation innovation projects to develop clean-slate solutions,

- Communicate your direction clearly in order to defuse internal opposition.

- Manage reverse innovation activities as disciplined experiments, like a Lean Startup