Thales’ history dates back over a century! The founders slowly built remarkable cohesion and strength through careful planning and ensuring an ability to adapt the structures to prevailing conditions. The roots originate from France and is now referred to as one of the world leading providers of technological solutions.

Over the years Thales has implemented many growth strategies, and the table below draws notice to some of the approaches taken in order to become a multi-domestic company. A firm’s entry strategy plays an essential role in determining the triumphant nature of a firm’s internationalisation process, so it’s useful to see how they approached each market.

It’s helpful to note that Thales’ multi-domestic presence differs from most other global companies. Global implies a company has headquarters in more than one country, are likely to be highly centralised and offer minimal adaptation to other cultures. Whereas a multi-domestic firm has headquarters in multiple countries and are more likely to adapt to cultures, despite the cost of doing so. Moreover, it has been argued that opting for a multi-domestic strategy yields a more significant competitive advantage as it chooses markets with the potential to maximise the returns.

| Year | Sector | Geographical focus | Entry mode | Ownership |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | Defence | Middle East | Exports | N/A |

| 1983 | Civil Telecommunications / Defence | Global | Mergers and Acquisitions | Joint (Thomson-CSF and Alcatel) |

| 1989 | Defence | Europe | Mergers and Acquisitions | Joint (Thomson-CSF and Alcatel) |

| 1996 | Ground Transport | Europe | Acquisition | Sole |

| 1998 | Defence | France | Acquisition | Joint (Thomson-CSF and Societe Commune de Satellites) |

| 1998 | Satellite | Acquisition | Joint (Thomson-CSF and Alcatel) | |

| 2000 | Telecommunications | UK | Takeover | Sole |

| 2000 | Defence | Transatlantic | Joint Venture | Joint (Thales and Raytheon) |

| 2007 | Naval | France | Stakeholder | 25% stake in DCNS |

| 2007 | Ground Transport | China | Joint Venture | Joint (Thales and Alcatel) |

| 2014 | All Sectors | Global | Greenfield | Sole |

| 2016 | Airspace | Norway | Greenfield | Sole |

| 2016 | Civil /defence | UK | Strategic Partnership | Joint (Thales and ASV) |

| 2017 | Telecommunications | France | Acquisition | Sole |

| 2017 | Civil / Telecommunication | Asia | Greenfield | Sole |

| 2018 | Civil | Netherlands | Acquisition | Sole |

Note: Original Table based on data collected from Thales Group(2018b)

Pioneering at the Turn of the 20th Century

1970-1980’s

Between 1970-1980 Thomson-CSF gained access to a vast number of export contracts located in the Middle East, with the oil crises which occurred in 1973 and 1979 Thales diversified into telephone switchgear, silicone semiconductors and medical imaging. This relatively early stage of internationalisation demonstrates Thales’ low commitment to the Middle East with an uncertain and temperamental sector, with no possibility of determining long-term success.

In order to build on this commitment per the Uppsala model, knowledge must be obtained in order to implement successful strategies at the firm and team levels. According to Laurens et al. (2014), this can be achieved by engaging in a TS internationalisation strategy whereas this stage of internationalisation was an HBE strategy.

1980-1990’s

The 80’s through to mid 90’s was a time of strategic refocusing on professional and defence electronics. In 1982 when Thomson SA was very weak with a business portfolio highly diversified and many insignificant market shares, too small for any to be profitable, debt remained high which meant that action needed to be taken.

In order to achieve this, a substantial amount of resources were invested into civil telecommunications through the 1983 agreement with CGE alongside medical imaging which the company sold to General Electric in 1987. Moreover, the semiconductor businesses merged with those from the Italian grouped called IRIFimeccanica in 1987 which formed the company SGS-Thompson. With this, focus shifted to managing financial activities and managing cash flows from major export contracts.

The French Prime Minister, Michot (2004) conducted research which led to identifying the role of the defence and space industries produce revenues of €25 billion, trade equating to €8 billion and exports representing almost 70% of all outputs.

Between 1990-1993 this business was overtaken by Credit Lyonnais in exchange for a stake in the bank so that Thales could continue to grow through mergers and acquisitions (M&A). Cutbacks as a result of this debt were mainly evident in the defence sector, and this debt also caused ongoing exports to close in order to preserve and maintain margins. With this Thomson-CSF developed a proactive policy implemented mostly in Europe and acquired a defence electronics business previously held by Philips groups in 1999.

After this time, Thales saw significant growth as a result of these M&A outside of France which resulted in non-French subsidiary revenue rises of 5% to 25%. Within 1996-1997 the shares previously held within SGS-Thompson (now ST Microelectronics) were divested, and these capital gains were used to finance continued international growth.

1998 represents the year of privatisation for Thomson-CSF. Where the top three competitors including that of Alcatel, Dassault Industries, Thomson-CSF and Thomson SA all reached an agreement. This agreement created a new entity which would merge professional and electronic defence businesses owned by Alcatel, and Dassault Elecronique with Thomson-CSF, and the satellite businesses of Alcatel, Aerospatiale and Tomson-CSF are merged to form Alcatel Space. This enables Thomson-CSF to diversify its business and gain a stronger position in defence and industrial electronics while increasing its presence within Europe.

At the end of all the mergers the French States interest reduced from 58% to 40% and these reduced shares were taken on by Alcatel and Dassault Industries. Around the same time, Thales also engaged in an international venture as they acquired 100% of ADI Ltd who were based in Australia, which showed eager growth from Thales, as this deal had a worth of €1.89 Million.

Moving into the 21st Century

2000-2010

Post-privatisation the group adopted a multi-domestic strategy within its defence markets were within the 1990’s vast and rapid expansion to South Africa, Australia, South Korea and Singapore. In 2000 there was a friendly takeover of the UK company previously known as Racal Electronics, this meant that the UK became the Groups second-largest “domestic” base and with this changed their name to Thales. When looking at the number of acquisitions and rapid growth of the group’s portfolio, strategic reviews outlined the importance of civil applications (particularly in mobile applications). The response to this included the establishment of three new business areas as of July that year – defences, aerospace and information technology and services (IT&S).

In 2000 the new structure was designed in order to leverage the group’s dual technology expertise and focus on its strategic development in their civil markets. To finish off the year come December, Thales formed the first joint venture within the defence sector with the American company Raytheon.

There were a large number of geopolitical and economic upheavals following September 2001, with this Thales aimed to strengthen its focus on the intensive technology segments within their defence markets. Alongside this, they also grew its role as prime contractor and service provider to meet the needs of client countries. This year also demonstrated growth in Singapore for Thales as they increased their stake in Avimo Group Ltd from 41.9% to 93.7% costing them €1.26 Million.

Continuing to pursue the multi-domestic strategy, Thales gained control of several defence and aerospace subsidiaries they formally held in joint ventures. Through their SHEILD initiative, Thales continued to divest non-strategic civil business in order to consolidate its capabilities in the security markets. The SHEILD initiative provides defence systems to anticipate domestic and foreign protectorates from airborne attacks.

In 2004 this focus on civil business almost at a close Thales announced a new organisation which consisted of six divisions, each of which were defined according to its representative markets in order to successfully implement common technologies. With this Thales acquired a minority stake in Canesta Inc based in the USA in 2005 while creating big plans for the company in coming years (Zephyr, 2018).

2007 was a year representing a new chapter of Thales’ history. With the transfer of transport, security and space activities from its partner, Alcatel-Lucent Thales was perceived as bigger and better than ever and had increased revenues, more employees, and complementary skills. These skills made Thales a significant world player with exceptional technological capabilities and became a leader in mission-critical information systems serving three markets, defence, aerospace, and security.

This year also entailed a signing of an agreement with the French naval player in DCNS and was worth €500,000. This deal bought Thales a 25% stake in the company and become an industry stakeholder-partner and gained access to naval credentials both on vital European programmes alongside many foreign export contracts.

A couple of years later in 2009, Dassault-Aviation acquired Alcatel-Lucent’s stake in Thales and is now the private shareholder and industry partner of the group. This same year Thales acquired 95% of an Israeli firm called CMT Medical Technologies, this acquisition had a worth of over €20 million.

2011-2018

More recently, however, there have been a number of strategic moves implemented all over the world. For instance, in 2014 Thales opened up an innovation centre in Singapore, their first outside of Europe. This expansion could have been a result of hiring Patrice Caine as CEO as Lin, and Liu (2012) argue a firm may experience an increase or reduction in internationalising with the change of successors, but these changes can be perceived as costly and risky which can also act as an obstacle when internationalising. That same year Thales also increased their stake in Amper Programas de electronica y Comunicaciones from 49% to 100%.

In the following years, with the aim of increasing their footprint in India Thales increased their purchasing policies to get more Indian companies as key suppliers thus developing their supply chain.

Linking back to the change of successors the introduction of a new CEO can also result in more money being invested in foreign countries, thus leading to increased revenues and profits.

Summary

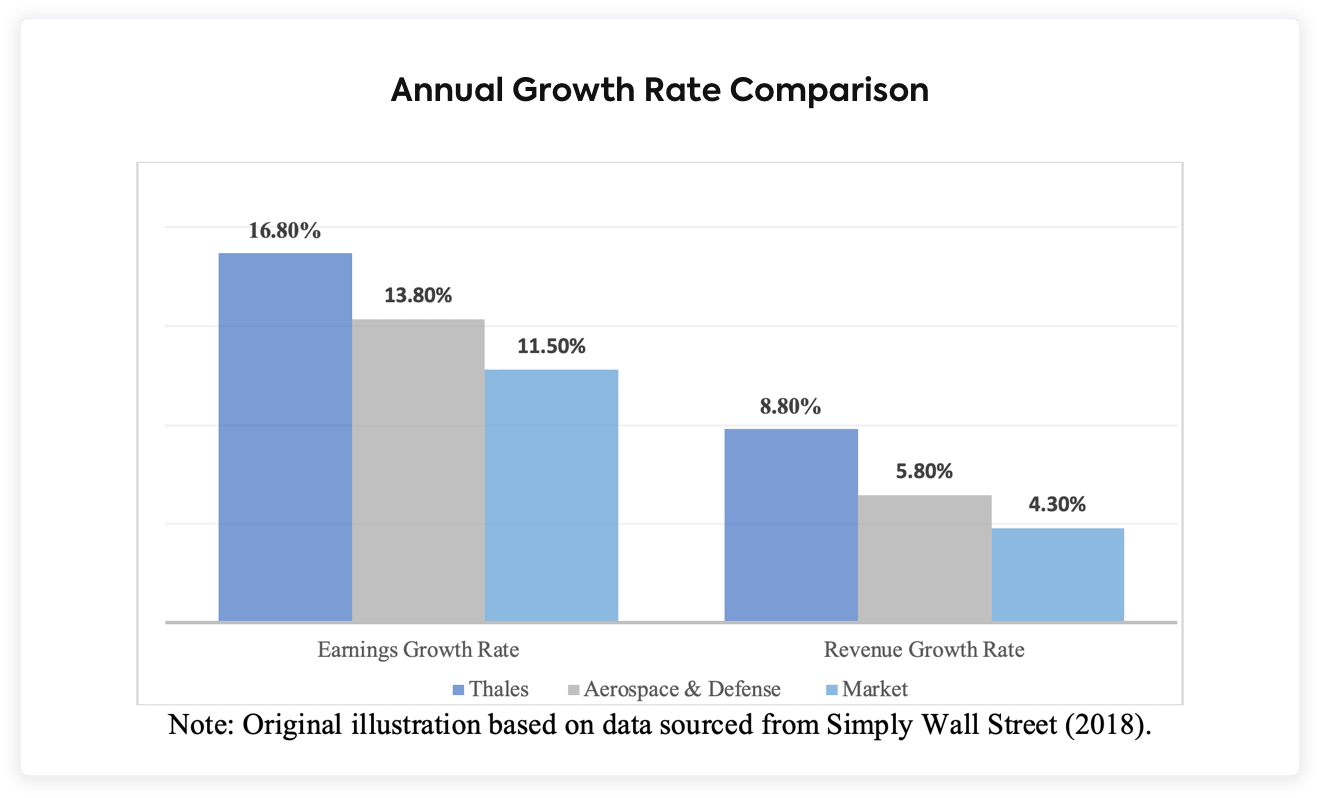

Thales is an interesting business with a history of good strategic decisions. As the graph above shows, their growth was significantly higher than that of the market – proof that their strategies for international growth were succeeding. The pressure will be on to continue development and growth for Thales, though they show no sign currently of slowing down – even at the time of this article being written (December 2019) it was just announced that The Australian Space Agency has signed an agreement with them.

So those international strategies are still in play, and are still working.

Need help building your own strategy?

Our strategy software makes it faster and easier to formulate a strategy, manage the execution and track the results. Book your demo today and get a strategy plan template tailored to your organization.